|

LAM SON 719 by Maj. Gen. Nguyen Duy Hinh Published by U.S. Army Center Of Military History

Contents

Glossary

LAM SON 719

CHAPTER III

The Planning Phase

How It All StartedTo the South Vietnamese political and military leaders, the Ho Chi Minh Trail had always been like a thorn in the back to be removed at any cost whenever there was a chancİ The possibility that something could be done about it began to take shape as the war intensified and U.S. combat forces helped regain the military initiative in 1966.

One of the leading Vietnamese strategists, General Cao Van Vien,

who was both Chairman of the Joint General Staff and Minister of

Defense at that time, was the first to advocate the severance of

the Communist lifeline. In a testimony given before members of the

National Leadership Committee, who ruled the country from June

1965 to September 1967, General Vien propounded an offensive

strategy, called the "strategy of isolation and severance" for the

effective defense of South Vietnam. This was in essence a two

pronged strategy aimed at isolating the Communist infrastructure

and guerrillas from the population within South Vietnam by

pacification on the one hand, and severing North Vietnam's

umbilical cord with its southern battlegrounds on the other. To

implement this severance action, he proposed to invade North

Vietnam's southern panhandle with the objective of seizing the city

of Vinh, the northern terminal of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and at the

same time establishing a strong defense line across northern Quang

Tri Province to run the entire length of National Route N÷ 9 from

the eastern coast to the Mekong River bank. This operation assumed

the participation of U.S. and other Free World Military Assistance

Forces. The attack against the two southernmost North Vietnamese

provinces - Thanh Hoa and Nghe An - and their

General Vien's concept remained only that because South Vietnam was unable to perform this momentous task all by itself. In early January 1971, General Crighton W. Abrams, COMUSMACV, called on General Vien at the JGS and suggested an operation into lower Laos. With the unrealized concept still nurtured in his mind, General Vien gladly agreed. Meeting with General Vien again a few days later, General Abrams explained his concept of the operation on a map. U.S. forces were to clear the way to the border by conducting an operation inside South Vietnam. The main effort was to be conducted by RVNAF airborne and armor forces along Route N÷ 9 in coordination with a heliborne assault into Tchepone. The purpose was to search and destroy base area 604. Other RVAAF units would be employed to cover the northern and southern flanks of the main effort. For the support of the operation, maximum U.S. assets would be provided. After searching and destroying base area 604, ARVN forces would shift their effort toward base area 611. At the end of the meeting, both General Abrams and General Vien agreed to have staff officers work out an operational plan. General Vien then reported his discussions with General Abrams to President Nguyen Van Thieu because he knew this cross-border operation was going to have international repercussions. Being a military man himself and well versed in military strategy, President Thieu immediately approved the operation.

Recognizing the political realities, General Vien had long since

abandoned the idea of an invasion of North Vietnam as part of an

operation to sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail, but still his concept

differed somewhat from that presented by General Abrams. General

Vien advocated

In mid January the J-3, JGS, Colonel Tran Dinh Tho, and his MACV

counterpart flew to Da Nang. Colonel Tho's mission was to brief

Lieutenant General Hoang Xuan Lam, Commander of I Corps and MR-l

on the concept of the operation. The meeting took place discreetly

at Headquarters, US XXIV Corps. General Lam was taken to a private

briefing room where, in front of a general situation map, Colonel

Tho explained how the operation was to be conducted as conceived by

the Joint General Staff(2). The

main effort of the operation, he said, was to be launched along

National Route N÷ 9 into Laos with the objective of cutting the Ho

Chi Minh Trail in the region of base area 604 and destroying all

enemy installations and supplies stored therİ After this mission

had been accomplished, the operational forces were to move south

and sweep through base area 611 to further create havoc to the

enemy's logistic system before returning to South Vietnam. This

operation was to be conducted and controlled by the I Corps Command

which, in addition to its organic units, would be augmented by the

entire Airborne Division and two Marine brigades. The third Marine

brigade and the Marine Division Headquarters would be available if

required. As to U.S. forces, they were going to conduct operations

on the RVN side of the border and provide the ARVN operating forces

with artillery, helilift and tactical air support. This concept of

operations thus coincided in near totality with the one initially

proposed by COMUSMACV.

On 17 January, planning guidance was provided by I Corps and U.S. XXIV Corps to participating units under the guise of "Plans for the 1971 Spring-Sumer Campaign" and on 21 January, General Lam and General Sutherland flew to Saigon, where, during a meeting at MACV Headquarters, they submitted the plan to the Chairman of the JGS and the MACV Commander(3). Intelligence estimates on which the detailed operational concept was formulated were also carefully reviewed. Subsequently on the same day, General Lam personally presented his operational plan to President Thieĝ

The Basic Operational Plan

The combined operation was code named LAM SON 719(4). It was to be executed in four phases

during an indefinite period of time with the objective of

destroying enemy forces and stockpiles and cutting enemy lines of

communications in base areas 604 and 61l.

(5)

Also during Phase II, the U.S. 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) was to continue operations west of Quang Tri Province and the U.S. 101st ABN Division (Airmobile) was to continue security operations as during Phase I and provide reinforcements and combat support as required. The ARVN "Black Panther" (reconnaissance) company, 1st Infantry Division, in the meantime, was to be attached to the U.S. 101st ABN Division and employed in rescue missions, if required, to extract U.S. crew members shot down in Laos. Phase III was to be initiated after the successful occupation of Tchepone. It was to be the exploitation phase during which search operations would be expanded to destroy enemy bases and stockpiles. The ABN Division would search the area of Tchepone while the 1st Infantry Division would conduct search operations to the south. The 1st Ranger Group, meanwhile, would continue holding blocking positions to the north. During Phase III, the mission of U.S. forces was unchanged; they would continue to provide fire support, helilift and tactical and strategic air for ARVN units.

Phase IV was the withdrawal phasİ On order, I Corps forces were

to withdraw toward the border by one of two alternate routes called

Options 1 and 2. In Option 1, the ABN Division and the 1st Armor

Brigade were to withdraw to Objective A Luoi to support and cover

the 1st Infantry Division which was to attack and search the

western part of base area 611 then move on southeastward, followed

by the ABN Division. In the meantime, the 1st Armor Brigade,

augmented by the 1st Ranger Group from its northern positions and

having been separated from the ABN Division, was to withdraw toward

Khe Sanh along Route N÷ 9. The Marine 147th and 258th Brigades

were to conduct operations into the Laotian salient toward

Objective Ngok Tovak at the same time as the 1st Infantry Division

began its attack to the southeast. Option 2 differed from Option 1

only during the last stage of the withdrawal when, after sweeping

through base area 611, the 1st Infantry Division, to be followed by

the ABN Division, was to

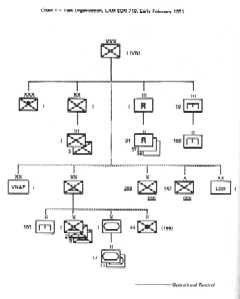

On 22 January, XXIV Corps and I Corps completed preparation of their operational orders. On DDDay, 30 January the Forward CP of I Corps was to be established at Dong Ha; it was to include a small command element to be located at Ham Nghi FSB, south of Khe Sanh. The Forward CP of the U.S. XXIV Corps was to move to Quang Tri combat base the day beforİ The I Corps forces were to cross the border on 8 February. During a combined briefing session held at Dong Ha on 2 February, the I Corps operation orders were disseminated to all participating units (6). (Chart 1)

To assist in the execution of LAM SON 719, MACV planned a diversion in the form of a maneuver involving U.S. naval and marine units off the coast of Thanh Hoa Province (North Vietnam).

Division Planning and PreparationsThe main effort of LAM SON 719 was assigned to the Airborne Division and on 18 January 1971, during a meeting at I Corps Headquarters, the division commander, Lieutenant General Du Quoc Dong, learned this for the first timİ He immediately ordered his division, at the ABN Division rear base in Saigon to begin preparations for deployment. Meanwhile, the U.S. advisory team on 27 January visited headquarters, U.S. XXIV Corps, to receive first hand briefings and report on ABN preparations. ABN units deployed on an operation in War Zone C (north of Tay Ninh) were withdrawn to receive additional training by U.S. advisers on communications and the employment of U.S. gunships and supply and medevac helicopters, as well as air-ground communications with supporting U.S. tactical aircraft.

General Dong flew to Dong Ha on 1 February 1971 and was followed

during the next few days by his staff, the U.S. ABN Division

advisory team, and combat and support units.

The combat plan developed by the Airborne Division called for successive heliborne operations to occupy Objectives 30, 31 and A Luoi in coordination with an armor-infantry thrust along Route N÷ 9. Intermediate objectives, on which fire support bases would be established, would be seized in the advance to Tchepone, after which battalion sized blocking positions would be occupied around Tchepone. The heliborne operations to occupy A Luoi and Tchepone would be conducted as soon as the armor-infantry thrust progressed near the objectives. This was to be a coordinated advance so timed as to provide immediate link-up at the objectives. (Map 11) Initially, the armor-infantry thrust consisted of two squadrons, the 11th and 17th of the 1st Armor Brigade, the 1st Airborne Brigade (with its three battalions: 1st, 8th and 9th), the 44th Artillery Battalion (155-mm) and the 101st Engineer Battalion. This task force was to advance along Route N÷ 9, repair roads as it moved and link-up with heliborne units. The 3d Airborne Brigade (three battalions: 2d, 3d and 6th) would be the heliborne force assigned to occupy objectives and establish FSBs north of the road. For the assault on Tchepone, the mission was given to the 2nd Airborne Brigade which consisted of three battalions, the 5th, 7th and 11th. The troop pick-up point for airborne operations would be Ham Nghi Basİ The Airborne Division operation plan was presented to Lt. General Hoang Xuan Lam on 3 February who immediately approved it in principle.

Of the two Marine brigades to be provided by the JGS, the 258th

Brigade with one artillery and three infantry battalions was

operating in an area southwest of Quang Tr¸ The other brigade,

the 147th after regrouping its detached units, completed its

movement by C-130 to Dong Ha on 3 February. Both brigades were to

be employed as I Corps reserves and given the temporary mission of

security for ARVN forces on the RVN side of the border.

S. SupportIt was apparent that due to the lack of helicopters, tactical air and long range artillery, I Corps could not conduct such a large scale operation away from its support bases without assistance. United States support was therefore required, not only to compensate for I Corps' lack of assets but also to provide the kind of mobility and firepower needed for combat against a heavily defended enemy stronghold in rugged terrain. Therefore, the U.S. XXIV Corps was charged with planning for this substantial support.

An outstanding feature of LAM SON 719 was the conspicuous absence

of U.S. combat troops and U.S. advisers who were not authorized to

go into

The U.S. 108th Artillery Group received the mission of augmenting the firepower of I Corps Artillery. This group consisted of the 8th Battalion, 4th Artillery (with four 8-inch howitzers and eight 175-mm guns), the 2d Battalion, 94th Artillery (with the same number of artillery pieces), and B-Battery, 1st Battalion, 396th Artillery (with four 175-mm guns). As required, the 108th Artillery Group could be augmented by the 5th Battalion, 4th Artillery (with eighteen 155-mm self-propelled howitzers), which was the direct support unit of the U.S. 1st Infantry Brigade (Mechanized).

Procedures for coordination and liaison were clearly established.

Fire coordination was to be effected at I Corps FSCC between fire

support elements of I Corps and XXIV Corps, and communications with

I Corps artillery was to be maintained through U.S. advisers.

Plans were also made to provide for close coordination between

supporting and supported units. This was done by an exchange of

liaison officers between the U.S. 108th Artillery Group and ARVN

infantry divisions and brigades operating separately. Fire support

requests from ARVN units in Laos could be routed through either one

of two alternate channels. The first channel was from requesting

units to division or separate command posts where the U.S. 108th

Artillery Group's liaison officers would receive and

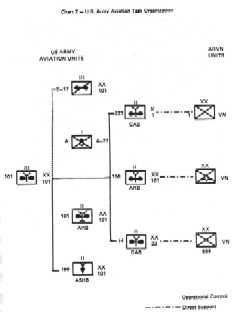

Of prime importance to the entire operation was the mobility support

provided by United States helicopters of all types. The U.S.

101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) was assigned this support

responsibility. Having to continue its current missions inside

South Vietnam which were greatly expanded due to the redeployment

of a number of ARVN units and to provide operational support in

lower Laos at the same time, the 101st Airborne Division obviously

could not meet all the requirements with its organic assets, so the

division was augmented with four Assault Helicopter Companies (UH-

lH), two Assault Support Helicopter Companies (CH-47), two Air

Cavalry Troops and two Assault Helicopter battalion headquarters,

all detached from other U.S. divisions. This reinforcement was to

be more substantial on days when special requirements arosİ Each

U.S. assault helicopter battalion was made responsible for

providing direct support to an ARVN major unit. Thus the 158th

Assault Helicopter Battalion was assigned to support the ARVN

Airborne Division and its reinforcements and the 223d Combat

Assault Battalion was to pr6vide support for the ARVN 1st Infantry

Division while the 14th Combat Assault Battalion would support the

Vietnamese Marine brigades. Each of these support battalions was

to attach a liaison team to the ARVN unit to be supported and each

U.S battalion commander was required to visit the ARVN unit he

supported every daÜ In case additional support units were

provided, they would be placed under the operational control of

these commanders. The commander of the 101st Aviation Group, 101st

Airborne Division was to exercise operational control over all

assault, assault support and aerial weapons helicopter units

(Chart 2). In addition, an

Assistant Commander of the 101st Airborne Division was designated

as the aviation support coordinator.

To solve problems related to tactical air support, certain flexible arrangements were madİ An airborne command and control center of the United States 7th Air Force (AFCCC) was to operate around the clock aboard a C-130 aircraft to receive support requests, provide guidance for preplanned tactical air sorties, to make decisions on the employment of assets, and to ensure that additional sorties would be available in case of emergency. All forward air controller (FAC) teams, each assigned a Vietnamese interpreter, were to cover the areas of operation assigned to ARVN divisions and separate brigades. Initially, 200 tactical air sorties were planned for, each daÜ Emergency tactical air support requests would be initiated by ground units and sent to the airborne FAC team which would relay them to the 7th Air Force AFCCC, also airborne, for immediate action. Preplanned sorties would have to be requested through the normal channel which went from the Tactical Air Control Parties (TACP), attached to ARVN divisions, to I Corps Fire Co-ordination Control Center/Direct Air Support Center (FSCC/DASC) and from there to the XXIV Corps Forward Direct Air Support Center at Quang Tr¸ To facilitate air support missions in bad weather or at night, an air support radar team (ASRT) of the U.S. Marines at Quang Tri would be provided at Khe sanh from where it could cover the entire area of operation in lower Laos. A number of U.S. naval air sorties to be launched from aircraft carriers USNS Hancock, Kitty Hawk and Ranger was also planned. Finally, LAM SON 719 was to receive the highest priority in strategic air sorties provided by the Unites States Strategic Air Command.

Solving Logistic Problems

In addition to combat and combat support planning, an important

area that required extensive pre-arrangements was logistics.

Unfortunately, the ARVN 1st Area Logistics Command, which was

responsible for logistical support for I Corps and MR-l, was

excluded from the operational planning staff because of security

and restrictive measures. Therefore, when this, logistic command

received orders to make preparations

During the initial period, no significant difficulties were encountered by U.S. logistic units in supplying ARVN forces because most supply items were similar with the exception of some special types of ammunition, for example 57-mm recoilless, and more particularly, combat rations. The ammunition items were no longer available in the U.S. supply system and ARVN combat rations were radically different from U.S. C-rations. As a result adequate ARVN combat rations were immediately shipped to class I supply points operated by United States forward support areas.

In air transportation, the two existing airfields at Quang Tri and Dong Ha were ready for immediate usİ The abandoned airstrip at Khe Sanh, however, needed extensive repairs by U.S. engineer units and was scheduled to become operational on D+6 to accommodate C-130 cargo planes. Several U.S. C-130 planes were also earmarked for the ARVN to transport emergency supplies directly to Khe Sanh. Due to the sizable quantity of helicopters required to support the operation, the supply of aviation fuel was an important problem. ARVN quartermaster units were assigned additional assets for the transportation of fuels, and the establishment of forward storage facilities and supply points.

To move supplies to forward combat units operating along Route N÷

9, ground transportation was planned. For those units operating

far from the road, helicopters would be used both for re-supply and

medical evacuation. As to the movement of heavy items of supply to

forward areas, the only means available would be large U.S. cargo

helicopters.

ObservationsThe entire planning process - and the resultant operations plan - for LAM SON 719 indicated a carefully considered decision arrived at by responsible U.S. and GVN political and military authorities. The authorities of each country - the US and the GVN - considered in their decisions the best intelligence available to them at the time and each approached the problem with the best interests of his own country in mind. Of course each was influenced by the political and military factors peculiar to his own country. Tchepone, the crossroads of enemy supply routes, appeared to be a well selected objective since all enemy logistic and infiltration movements south had to go through this areĠ According to intelligence reports, this was indeed an area where important enemy storage facilities were located. The time had finally arrived to sever by ground attacks the lifeline which had sustained enemy warring capabilities for so many years. This was a sound and bold decision following several years of reconnaissance and interdiction efforts from the air. The time frame selected for the operation was also appropriate in that the dry season in the Laotian panhandle had begun three months earlier. After his substantial losses in Cambodia during 1970, the enemy was using the dry season to the maximum for the movement of replacements south and to replenish his supplies; the enemy was conducting an aggressive "logistic offensive." The amount of supplies in transit and in these storage facilities was substantial and if we succeeded in destroying them, the blow on the enemy would be most devastating. He would be in serious trouble, not only from our spoiling actions during the remaining three months of the dry season, but also because time was running out for the movement of supplies for that year.

Despite the continuation of redeployments, United States military

presence in South Vietnam was still substantial enough to support a

large scale offensive by the ARVN. If this offensive were

deferred, U.S. support would no longer be as adequate and as

effective. This was

Once the decision was made, the speed with which planning and preparations progressed was amazing. Only two weeks after planning guidance was received, operational orders had been developed by I Corps and XXIV Corps. This was indicative of how close and effective cooperation and coordination between U.S. and ARVN staffs had been. The exchange of intelligence proved to be particularly beneficial to ARVN forces. Lacking long range reconnaissance facilities, the ARVN intelligence system could not provide adequate data on the Ho Chi Minh trail and North Vietnam. It was obvious that almost all information concerning enemy capabilities in the target area had to be supplied by the United States. Combat support provided by the U.S. XXIV Corps for I Corps was another indication of the outstanding support provided by MACV. The I Corps unit commanders who were to participate in the operation felt encouraged and unusually enthusiastic because of this. To them, this was an opportunity not only to prove I Corps combat effectiveness but also to compete with their colleagues of III and IV Corps who had participated in the Cambodia incursion the previous year. Finally, the fact that no U.S. combat troops were to cross the border and that even U.S. advisers were precluded from the operation made the role of ARVN units even more prominent.

In spite of the sound decision, the effective cooperation and

coordination between the RVNAF and MACV and the support allocated

by the United States, several problem areas cropped up during the

planning phase which should receive special attention. First, the

entire process of planning and operational preparations appeared to

have taken place in a great rush. Considering the scale of the

operation and the importance of the objectives, the time involved

for planning might have been too short. To ensure utmost secrecy,

participating units were given only a short time to prepare. In

the face of such a difficult campaign which was to be conducted

over unfamiliar terrain, the question that naturally arose was:

were I Corps units prepared to

Next was the tactic of establishing fire support bases. In view of the single axis available to progress through mountains, the effective control of the area of operation and the conduct of search activities depended on the capability of our forces being deployed on both sides of the road, north and south. In our case, the operational plan called for the advance of infantry forces through a series of fire support bases. Each new leap forward necessarily required an additional number of these bases. The use of fire support bases had been successful in South Vietnam but this success depended a great deal on the over-whelming firepower and initiative of United States forces in the face of a less endowed enemÜ To be effective in lower Laos, it was apparent that fire support bases would have to enjoy the same conditions. The question was: would it be feasible? If it was not - without the benefit of firepower and initiative in the area of operation - fire support bases were apt to become defensive positions tying down sizeable forces which otherwise might be used for offensive.

A comparison between friendly and enemy forces in lower Laos also

resulted in hard thinking even during the initial phasİ As

intelligence estimates had made it clear, enemy forces in the area

of operation included three infantry regiments, not to mention the

eight or so binh

In the effort to obtain the tactical advantage in the area of operations and to compensate for the lack of force superiority, the planners of LAM SON 719 expected too much from the support of United States tactical air and air cavalry gunships. The question that should have been asked then was: how effective would air power be in support of ground combat troops deep in the Truong Son mountain rangë If the bombings of North Vietnam had been an indication of this effectiveness, then were the results to be obtained exactly what we had desired? Over the years, the U.S. Air Force had bombed the Ho Chi Minh trail heavily. Was the effect of these bombings enough to paralyze the enemy's activities on the battlefields of South Vietnam and Cambodia? Too much was expected from airpower and this problem should have been weighed with caution by the planners.

Then there was the role to be played by helicopters. With the

exception of mechanized forces operating along Route N÷ 9 which

would be re-supplied by road transportation according to plans, all

other operational units would have to depend on helicopters for

movement of troops and artillery, supply and medical evacuation.

This was the only means practicable as long as these forces were

required to operate considerable distances from roads and fire

support bases. There was no doubt that

As the time approached for Ddday, however, ARVN and U.S. commanders and staffs alike appeared to be confident of success. As a testimony to this confidence, I think it appropriate to excerpt here a passage of the report filed by Colonel Arthur W. Pence, senior adviser of the Airborne Division. In this after- action report, Colonel Pence described the mood that prevailed during a meeting at Headquarters, U.S. XXIV Corps prior to Phase I of LAM SON 719. He wrote: "It was apparent at this time that United States intelligence felt that the operation would be lightly opposed and that a two day preparation of the area prior to DDDay by tactical air would effectively neutralize the enemy antiaircraft capability although the enemy was credited with having 170 to 200 antiaircraft weapons of mixed caliber in the operational areĠ The tank threat was considered minimal and the reinforcement capability was listed fourteen days for two divisions from north of the DMZ." (9)

The RVN military leaders thought that ARVN forces had a tough

mission ahead but would be able to carry it out with the support of

the United States. The decision had been madİ I Corps forces

were like the soldier on the firing line who had armed his rifle

and taken aim. All he had to do now was to squeeze the trigger.

(1) "Vietnam: What Next? The Strategy of Isolation," Military Review, April 1972. (2) After the exclusive briefing for General Lam, Colonel Cao Khac Nhat, G-3 I Corps, took Colonel Tho aside and told him, "Why exclude me from the briefing? I have already completed the operational plan." (3) This date was obtained from U.S. XXIV Corps After Action Report which records: "21 January: XXIV Corps/I Corps received approval of detailed concept." Ibid. p.3. (4) Lam Son was the birthplace of Le Loi, a national hero second only to Tran Hung Dao in popular reverence. Le Loi ejected the Chinese from Vietnam in the early 15th Century. (5) The directive given by U.S. XXIV Corps to the U.S. 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) and the Da Nang Support Command stated that these units should be prepared to provide support for I Corps operations forces for at least 90 days, in other words, until the onset of the Laotian rainy season in early May 1971. (6) For details on participating units, see Appendix (7) General Lam considered the Ranger Group adequate for this mission, which was to provide the main body early warning of any enemy force approaching on his flank and to delay and force him to concentrate until heavier combat power could be placed against him. It would have been advantageous to assign this mission to a mobile, armor equipped force, but not only did the rugged terrain preclude this, but General Lam needed his armor and his 1st Division for the main effort. Furthermore, he wanted to keep the 1st Division available for a sweep south through base area 611. (8) After Action Report on LAM SON 719; 1 April 1971, by Colonel Arthur W. Pence, p. 3. (9) After Action Report on LAM SON 719 dated 1 April 1971 by Colonel Arthur W. Pence, p. 2.

|